Taxation has been an emerging topic of corporate responsibility for over a decade. But unlike other areas such as environment, supply chain labour standards and human rights it has not yet matured from battleground to collaboration. Will 2017 be the year when tax and corporate responsibility come together? What are the emerging standards and initiatives and can they get beyond agreement on vague principles to dilemmas in practice? Could public country by country reporting build trust and understanding, or would it fuel more misunderstanding? And could the sustainable development goals help companies articulate how tax relates to investment and economic impact?

Taxation has been bubbling up as an area of controversy and reputation risk for big businesses for at least two decades. Following the financial crisis, the rising drumbeat of newspaper headlines, campaigns and exposés reached a critical pitch. According to surveys carried out by the Institute of Business Ethics, ‘corporate tax avoidance’ has consistently been the greatest business ethics concern amongst the UK public for the past four years (2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016).

NGOs such as ActionAid, Christian Aid and Oxfam have highlighted multinational tax as an issue in relation to development. In fact, as an NGO evaluation of their campaigning around the G8 summit in 2013 reflected: ‘The way the media focused on tax made it hard to talk about anything else [in the end]. It wasn’t in our control.’

The level of public attention paid to tax certainly contributed to the speed and ambition of the G20/OECD BEPS process, as well as other policy and regulatory responses, from the EC’s application of state aid rulings, the UK’s general anti-abuse rule (GAAR), the ‘Google tax’ and development of strict liability rules for offshore evasion. However, the public debate remains difficult, polarised and fraught with misunderstandings.

Tax has long been recognised as a corporate responsibility issue. One of the oldest sets of guidelines on responsible business, the OECD Guidelines for MNEs (http://mneguidelines.oecd.org), included taxation as a core area in its very first iteration in 1976. Similarly, the Sunshine Standards, an early forerunner of today’s Global Reporting standards (www.globalreporting.org), called on companies to report on ‘taxes paid to all jurisdictions, classified by type of tax’. However, the question of what users might do with this information, or more broadly how to assure the public that a company is taking a responsible approach to tax, has remained intractable (and largely unexplored).

In the meantime, other (equally difficult) issues concerning business and society – such as labour standards in supply chains, human rights around mining operations, climate change and bribery – have matured. They have gone from being fractious battlegrounds between businesses and NGOs to sustained dialogue and collaborations to share understanding, explore dilemmas, agree principles of good practice and work on longer term solutions to common problems.

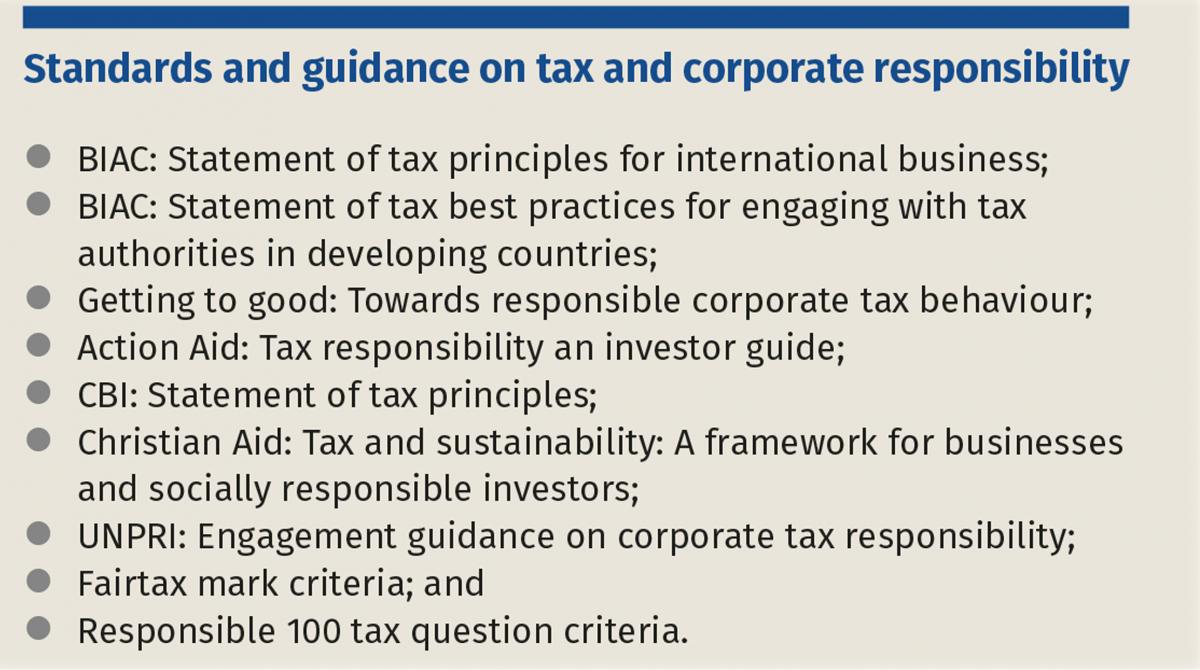

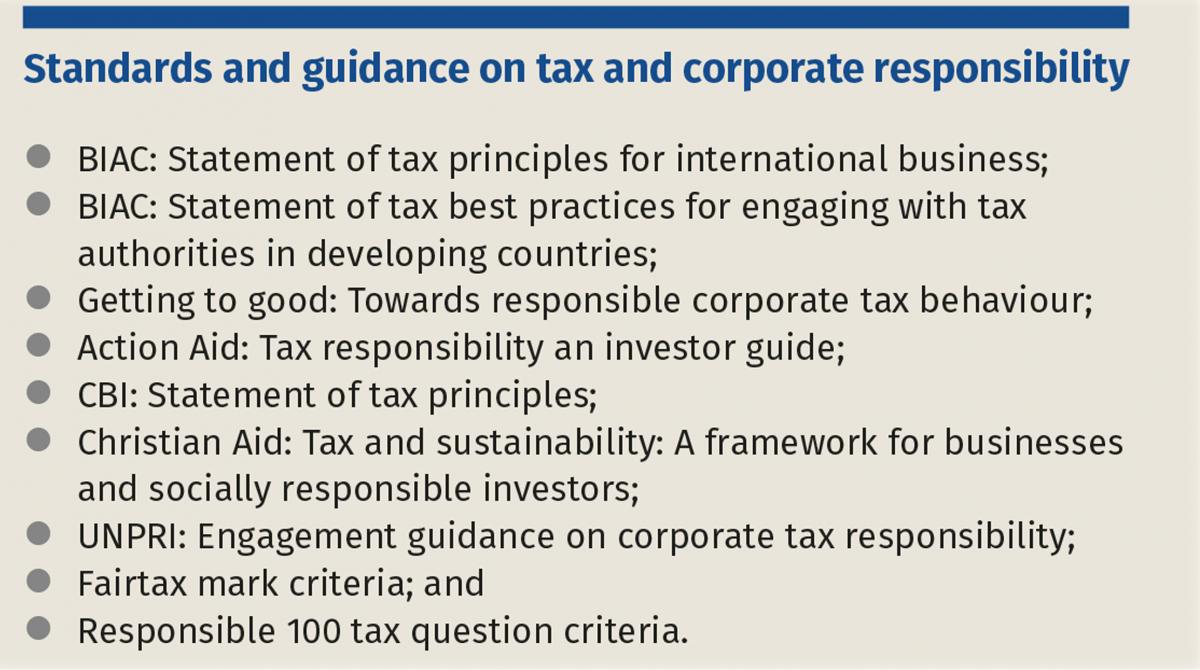

This has not happened on tax. While there can be broad agreement around principles such as that profits should be aligned to where value is created and that companies should not undertake ‘aggressive avoidance’, debates about what this means in practice tend to veer between ill-defined and acrimonious. In 2006, the think tank Sustainability published a review of the state of the debate on corporate responsibility and taxation (Beloe et al, 2006). The authors noted the growing levels of interest from the media, NGOs and the research community, but were surprised by the level of polarisation of the debate. Ten years later, the level of polarisation is if anything higher. The public appetite for tax exposés and scandals is not abating, while tax professionals are frustrated by the misunderstandings and exaggerated claims which shape the media and public debate. There have been some efforts to set out criteria for responsible tax behaviour, but they have not converged on a single view of responsible tax practice.

It is clear that paying tax is a core part of the way that a business fulfils its responsibility to society and secures its licence to operate. But what is less clear is whether there is much else to say on the matter than ‘we comply with the law’ (and its corollary, ‘if you don’t like the law then change it’).

When individual companies such as SABMiller, Paladin Mining, Associated British Foods, Google and Vodafone (and last year, even Oxfam’s trading arm) are hauled into the court of public opinion, they have responded with the ‘tax mantra’ that their tax affairs are ordinary, business driven and in full compliance with relevant legislation. These explanations, however, do not answer concerns about the fairness or solve the impossible task of living up to unclear expectations.

NGOs argue that the cure to the problem of unclear expectations is greater transparency. Companies should publish country by country (CBC) information, so that citizens can ‘see for themselves what tax multinationals pay’. BEPs Action 13 requires that companies submit CBC reports, but these are only meant to be shared between tax authorities as a risk assessment mechanism for directing audit attention. Campaigners remain committed to the idea of public country by country reporting. This is still being pursued through the European Parliament and last year the UK passed a Finance Bill including an amendment giving the Treasury power to switch on the requirement for public disclosure of tax filings in the future. Many tax practitioners remain wary and say that public CBC reporting will lead to even more confusion and unfounded criticism, undermining overall trust in the tax system. BIAC argues that: ‘Public disclosure of country by country reports has no clearly articulated specific purpose.’

Recent campaigning reports using available country by country information do little to allay these fears, and suggest that even if campaigners win the battle on public country by country reporting it is not clear that this will have the effect hoped for.

The Greens/European Free Alliance in the European Parliament compiled a partial country by country report on the clothing giant Inditex last year, and announced that they had found that the group ‘has saved at least €585m in taxes by using aggressive corporate tax avoidance techniques’. Similarly, Oxfam looked at data published by European banks under the CRD IV regulations and said that it shows massive profit shifting into tax havens.

These two reports take a common approach: comparing ratios of profits, turnover, employee numbers and tax in different locations. Far from being able to pinpoint aggressive avoidance, they demonstrate the limits of CbC data, with analysis that tends to view any departure from a homogenous ratio as evidence of profit shifting.

All this may suggest that the wisest course of action is for companies to say as little as possible about tax, as there is no way to win the public debate. However, discussions about who pays tax, and how, are only likely to intensify with new business models and digitisation. Hoping that tax as a corporate responsibility issue will go away seems foolhardy for business, while continuing to be guided by iconic transparency goals is equally short-sighted for NGOs.

Corporate responsibility is often thought of in simplistic, Pavlovian terms; consumers and investors motivated by ethical concerns and mobilised by NGO campaigns reward or punish companies for their social and environmental performance. In practice, though, this ‘watchdog’ model is rarely how corporate responsibility issues play out. Experience of other social, environmental and ethical concerns is that difficult issues don’t come with ready packaged solutions; corporate leadership and reputation driven action is not enough to solve them; and NGOs, the media and consumers don’t make adequate watchdogs. But what they can do is learn together, and sometimes help to change the nature of public debates and policy action (such as on climate change).

Debates about the role of business in society are increasingly being framed in terms of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) – a set of 17 ‘global goals’ for 2030 agreed by almost all the world’s nations through the UN. The SDGs are significant because they are universal. They don’t just focus on developing countries or on aid, but recognise the role of domestic revenues and private investment. They perhaps open up a window to a new dialogue on tax based on wider objectives such as tax certainty, building trust in the system and in enabling the more robust, honest and open debates needed for tax reforms both in developed and developing countries. Initiatives such as COVI’s ‘Responsible tax lab’, KPMG’s convenings on responsible tax, the work of Principles of Responsible Investment and the OECD’s Guidelines for MNEs are all exploring this territory.

Tax directors, while busy responding to the changes created by BEPS and the uncertainties of Brexit, are drawing up public statements explaining their tax strategy. At the same time, 70% of large businesses say they plan to embed the long-term perspective of the SDGs within five years. These are conversations that could do with being joined up internally and then externally.

Taxation has been an emerging topic of corporate responsibility for over a decade. But unlike other areas such as environment, supply chain labour standards and human rights it has not yet matured from battleground to collaboration. Will 2017 be the year when tax and corporate responsibility come together? What are the emerging standards and initiatives and can they get beyond agreement on vague principles to dilemmas in practice? Could public country by country reporting build trust and understanding, or would it fuel more misunderstanding? And could the sustainable development goals help companies articulate how tax relates to investment and economic impact?

Taxation has been bubbling up as an area of controversy and reputation risk for big businesses for at least two decades. Following the financial crisis, the rising drumbeat of newspaper headlines, campaigns and exposés reached a critical pitch. According to surveys carried out by the Institute of Business Ethics, ‘corporate tax avoidance’ has consistently been the greatest business ethics concern amongst the UK public for the past four years (2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016).

NGOs such as ActionAid, Christian Aid and Oxfam have highlighted multinational tax as an issue in relation to development. In fact, as an NGO evaluation of their campaigning around the G8 summit in 2013 reflected: ‘The way the media focused on tax made it hard to talk about anything else [in the end]. It wasn’t in our control.’

The level of public attention paid to tax certainly contributed to the speed and ambition of the G20/OECD BEPS process, as well as other policy and regulatory responses, from the EC’s application of state aid rulings, the UK’s general anti-abuse rule (GAAR), the ‘Google tax’ and development of strict liability rules for offshore evasion. However, the public debate remains difficult, polarised and fraught with misunderstandings.

Tax has long been recognised as a corporate responsibility issue. One of the oldest sets of guidelines on responsible business, the OECD Guidelines for MNEs (http://mneguidelines.oecd.org), included taxation as a core area in its very first iteration in 1976. Similarly, the Sunshine Standards, an early forerunner of today’s Global Reporting standards (www.globalreporting.org), called on companies to report on ‘taxes paid to all jurisdictions, classified by type of tax’. However, the question of what users might do with this information, or more broadly how to assure the public that a company is taking a responsible approach to tax, has remained intractable (and largely unexplored).

In the meantime, other (equally difficult) issues concerning business and society – such as labour standards in supply chains, human rights around mining operations, climate change and bribery – have matured. They have gone from being fractious battlegrounds between businesses and NGOs to sustained dialogue and collaborations to share understanding, explore dilemmas, agree principles of good practice and work on longer term solutions to common problems.

This has not happened on tax. While there can be broad agreement around principles such as that profits should be aligned to where value is created and that companies should not undertake ‘aggressive avoidance’, debates about what this means in practice tend to veer between ill-defined and acrimonious. In 2006, the think tank Sustainability published a review of the state of the debate on corporate responsibility and taxation (Beloe et al, 2006). The authors noted the growing levels of interest from the media, NGOs and the research community, but were surprised by the level of polarisation of the debate. Ten years later, the level of polarisation is if anything higher. The public appetite for tax exposés and scandals is not abating, while tax professionals are frustrated by the misunderstandings and exaggerated claims which shape the media and public debate. There have been some efforts to set out criteria for responsible tax behaviour, but they have not converged on a single view of responsible tax practice.

It is clear that paying tax is a core part of the way that a business fulfils its responsibility to society and secures its licence to operate. But what is less clear is whether there is much else to say on the matter than ‘we comply with the law’ (and its corollary, ‘if you don’t like the law then change it’).

When individual companies such as SABMiller, Paladin Mining, Associated British Foods, Google and Vodafone (and last year, even Oxfam’s trading arm) are hauled into the court of public opinion, they have responded with the ‘tax mantra’ that their tax affairs are ordinary, business driven and in full compliance with relevant legislation. These explanations, however, do not answer concerns about the fairness or solve the impossible task of living up to unclear expectations.

NGOs argue that the cure to the problem of unclear expectations is greater transparency. Companies should publish country by country (CBC) information, so that citizens can ‘see for themselves what tax multinationals pay’. BEPs Action 13 requires that companies submit CBC reports, but these are only meant to be shared between tax authorities as a risk assessment mechanism for directing audit attention. Campaigners remain committed to the idea of public country by country reporting. This is still being pursued through the European Parliament and last year the UK passed a Finance Bill including an amendment giving the Treasury power to switch on the requirement for public disclosure of tax filings in the future. Many tax practitioners remain wary and say that public CBC reporting will lead to even more confusion and unfounded criticism, undermining overall trust in the tax system. BIAC argues that: ‘Public disclosure of country by country reports has no clearly articulated specific purpose.’

Recent campaigning reports using available country by country information do little to allay these fears, and suggest that even if campaigners win the battle on public country by country reporting it is not clear that this will have the effect hoped for.

The Greens/European Free Alliance in the European Parliament compiled a partial country by country report on the clothing giant Inditex last year, and announced that they had found that the group ‘has saved at least €585m in taxes by using aggressive corporate tax avoidance techniques’. Similarly, Oxfam looked at data published by European banks under the CRD IV regulations and said that it shows massive profit shifting into tax havens.

These two reports take a common approach: comparing ratios of profits, turnover, employee numbers and tax in different locations. Far from being able to pinpoint aggressive avoidance, they demonstrate the limits of CbC data, with analysis that tends to view any departure from a homogenous ratio as evidence of profit shifting.

All this may suggest that the wisest course of action is for companies to say as little as possible about tax, as there is no way to win the public debate. However, discussions about who pays tax, and how, are only likely to intensify with new business models and digitisation. Hoping that tax as a corporate responsibility issue will go away seems foolhardy for business, while continuing to be guided by iconic transparency goals is equally short-sighted for NGOs.

Corporate responsibility is often thought of in simplistic, Pavlovian terms; consumers and investors motivated by ethical concerns and mobilised by NGO campaigns reward or punish companies for their social and environmental performance. In practice, though, this ‘watchdog’ model is rarely how corporate responsibility issues play out. Experience of other social, environmental and ethical concerns is that difficult issues don’t come with ready packaged solutions; corporate leadership and reputation driven action is not enough to solve them; and NGOs, the media and consumers don’t make adequate watchdogs. But what they can do is learn together, and sometimes help to change the nature of public debates and policy action (such as on climate change).

Debates about the role of business in society are increasingly being framed in terms of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) – a set of 17 ‘global goals’ for 2030 agreed by almost all the world’s nations through the UN. The SDGs are significant because they are universal. They don’t just focus on developing countries or on aid, but recognise the role of domestic revenues and private investment. They perhaps open up a window to a new dialogue on tax based on wider objectives such as tax certainty, building trust in the system and in enabling the more robust, honest and open debates needed for tax reforms both in developed and developing countries. Initiatives such as COVI’s ‘Responsible tax lab’, KPMG’s convenings on responsible tax, the work of Principles of Responsible Investment and the OECD’s Guidelines for MNEs are all exploring this territory.

Tax directors, while busy responding to the changes created by BEPS and the uncertainties of Brexit, are drawing up public statements explaining their tax strategy. At the same time, 70% of large businesses say they plan to embed the long-term perspective of the SDGs within five years. These are conversations that could do with being joined up internally and then externally.